Planting the Seeds: I’m a gamer from way back. In the seventies, my family moved from the country to a more-populated area. Across the street from our new home was a family with ten kids. One of them spied me reading The Two Towers on the school bus and suggested that meant I would probably like “gaming.” I did like gaming, of course. I loved board games like Scrabble, chess and Yahtzee and a wide variety of card games, but his expression implied he was referring to something outside the usual gaming experience. Intrigued, I badgered him to provide an example. All he had were six-sided dice, but he made them work. The idea that not all of the players participated in the same way – that one person in the group was tasked with role that was both administrative and creative – fascinated me. I wasn’t alone. My friend’s sample game soon expanded to included several of his brothers as well as one of mine. We were addicted. We played that game for years until college intervened. By that time, though, I was running my own game. Some of the original players continued along. Indeed, after a long hiatus, five of the original players were recently resurrected to game in an online Roll20 5th-Edition game that has persisted throughout the pandemic.

A Unique Perspective: We didn’t all play for the same reasons. Some of us were action junkies. Some enjoyed the camaraderie. Some loved the interactive storylines. The biggest draw for me, however, was using the magic system to solve puzzles in clever and unexpected ways.

Identifying the Problem: Given that focus, my biggest gripe with early “blue-book” D&D was that there was no underlying theory for how magic worked. Lack of theory was tolerable if the gamemaster was thoughtful and rigorous. In that case, my approach was to create predictability through precedent – that is, as a player, if I wanted to use the magic in a way I suspect might be viewed as problematic, I first created a situation where the GM was comfortable with a specific outcome to set the hook. Then I used the magic in the same way to solve the problem I was actually interested in to reel in the desired result.

A Unifying Theory: As a GM myself, though, I longed for something more. I wanted to know the nuts and bolts of how the magic worked. I wanted consistent principles applicable across situations. I wanted those details fleshed out enough so that I could plan ahead and know, without the bother of setting a precedent each time, how something – even something I hadn’t used before – would play out in practice. Such a system would enable players who take the time to understand the principles to be far more effective than those who just wanted to cast the occasional spell. They could design tests to determine aspects of how items worked and use those principles to actually design an item. One could still play a mage without learning the system, but a mage who took the extra time to understand the system would really stand out. I spent years designing the Spellbounds system, and I had a semi-regular group who play-tested it through the 80s and 90s. At last, mages were not utterly dependent on the vagaries of GM whim with respect to magical results. Players could now use magic strategically instead of reactively.

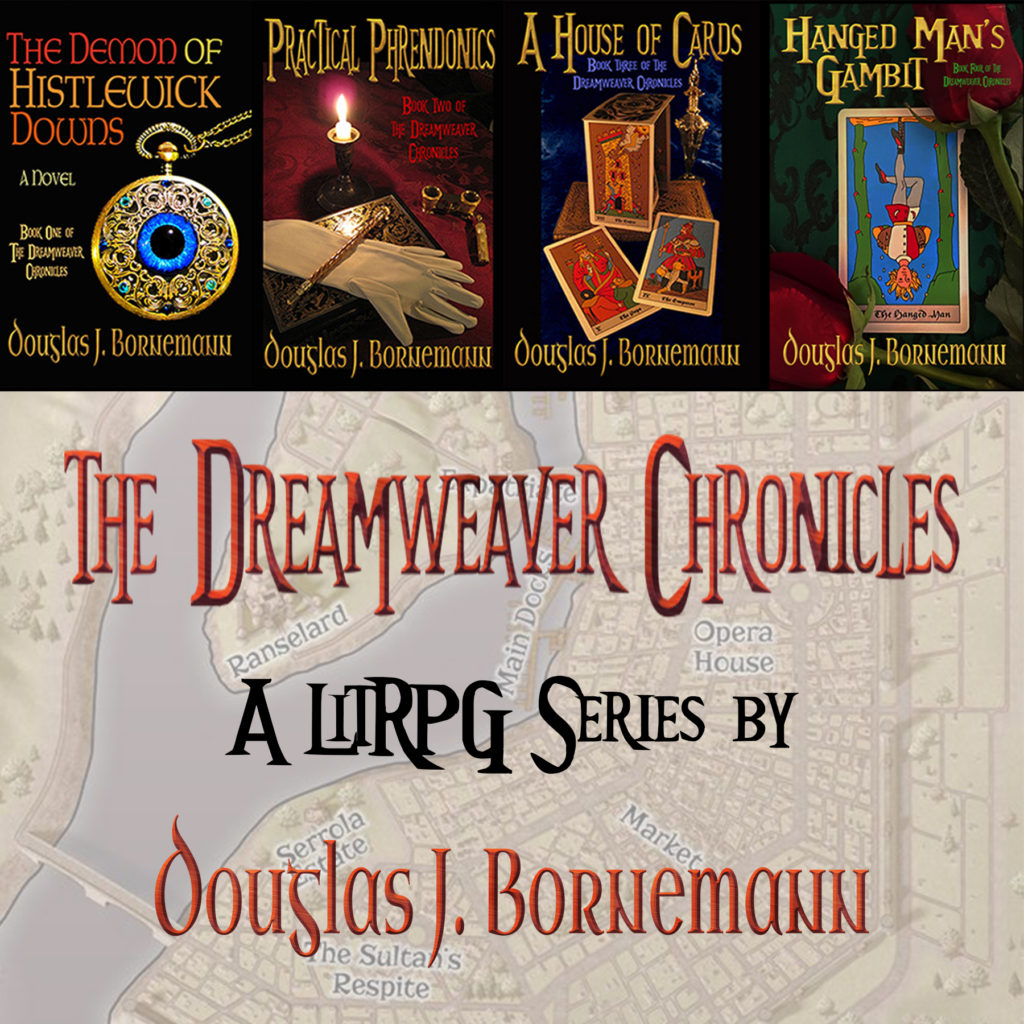

Changing Focus: Sadly, our move to California in 2002 put and end to that game. Online gaming tools weren’t well developed and they weren’t set up for my gaming system. By 2006, I had instead turned my creative impulses to writing fiction. World building was simplified by having a detailed magic system already in hand. Still, there was much to learn. From 2006 to 2011, I concentrated on writing the Heiromancer Trilogy, which consists of Practical Phrendonics, A House of Cards, and Hanged Man’s Gambit. (The trilogy is a single story divided into three parts, since that’s how long stories can be most easily managed in terms of editing and binding). I attended writers workshops to learn the basics of the craft. I found a professional editor who helped me learn the nuances of fiction writing. And through it all, I kept writing. All of those components were invaluable. While I was waiting for an editing slot for Practical Phrendonics, I wrote The Demon of Histlewick Downs, which serves as a standalone prelude to the trilogy. My editor reviewed the first few pages and suggested that I publish that book first, which made sense, since it comes first chronologically.

The Struggle to Fit In: The magic is integral throughout the series – the characters learn more about how it works as the stories progress. Categorizing the books as fantasy doesn’t really capture their essence, though. The term is too broad, and the available subgenres (epic fantasy, sword and sorcery, low fantasy, urban fantasy, paranormal fantasy) didn’t give the reader an adequate sense of what to expect.

Epiphany: Then, last month I happened across Sufficiently Advanced Magic, by Andrew Rowe and I learned a new term – LitRPG. You may already have heard of Ready Player One, by Ernest Cline, a classic LitRPG tale. LitRPG is a relatively new subgenre – the term was only coined in 2013, several years after my trilogy was already written. It refers to literary works where the advancement and system details play a major role in the story development. Often these stories take place in game settings. As in an actual RPG, the characters advance as the story progresses, and those details are considered features, not distractions. I devoured Andrew’s first series, and I relished the attention given to his magic system, particularly after having struggled with some of the same problems in my own system. In LitRPG, advancement and increasing system knowledge can be an explicit goal.

Coming Home: I think my books have finally found a kindred subgenre. While my series doesn’t embrace the “leveling” aspects as explicitly as some other LitRPG offerings, advancement and increasing use and knowledge of a detailed magic system is definitely a feature. Die-hard LitRPG fans may insist that the leveling is a quintessential LitRPG element – and those folks might consider my books to better fit the related GameLit fantasy subgenre. The difficulty is that purists might require those stories to explicitly include a game setting (like Jumanji, for example). In either case, I’m delighted that I can now point to books that share a similar genesis and approach.

Endgame: I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I enjoyed writing them.

(0)Dislikes

(0)Dislikes (0)

(0)